Written and Illustrated by Harriet Paintin and Hannah Kirmes-Daly

Following the night in the Sudanese camp, we hoped to visit the Syrian camp which is made up of fifteen men from a same village in Syria who have managed to resist attempts by the authorities to move them to the jungle an hour outside of Calais. Instead we found them perched on a platform next to a warehouse in tents and makeshift structures next to the port. We walked up to shouts of welcome from the group on men sitting outside a tent. In the middle was a man shaving with a little mirror. We sat down, and Hannah immediately took out her sketch book and began drawing him, ‘no no, not like this!’ He protested smilingly, wanting to present himself in the most attractive fashion for his portrait. Sitting in amongst the tents there was a little kettle heating up on a gas bottle stove, preparing the warm water for the next man to shave.

Hannah began communicating in her broken Arabic and passing round pieces of paper, encouraging the others to participate in the drawing while Ed and I took out our violins and played a couple of tunes. People began dancing, shouting and joking; the charged atmosphere swept us all up and carried us through. They played Syrian music on their phones and we got up to dance with them. Hand in hand we moved round and round in a circle, stumbling over the steps as they leapt and stamped and shouted.

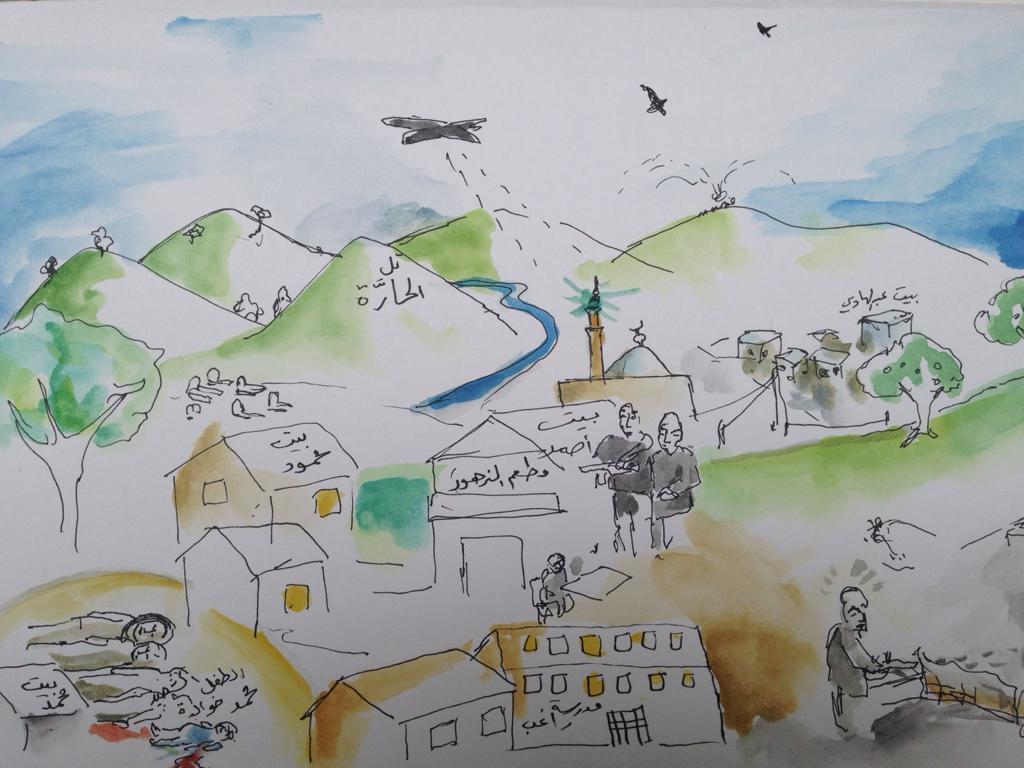

By sharing music, art, and dance we were now feeling at ease, familiar. Hannah sat with a small group, sketchbook on her lap, and impromptuly said, ‘tell me about your hometown, your village, what does it look like? I can draw it for you’.

They lent in:

‘There are the mountains, the river… the olive trees… and houses, my house is here… yes, the mosque’.

They began pointing out where their houses would be, showed us photos. They wrote their names in Arabic above their houses. Gradually the village took shape on the paper in front of us, and the story took a turn.

‘Then there are the planes, flying over… and the police, with their guns… the graveyard…’

‘Here a dead child, near my house. They died, the whole family… they were eating, in Ramadan… all the family died. Seven people. My house… BOOM! No house now. In the past, here was the house… Now, no house… bombs broken’.

One man started playing music on his phone, and sang. To us, to the image, but also to their hometown, ‘the olive trees, the olive trees…’

His eyes filled up with tears, ‘I want to go home, I want to return’.

But for many of these men there is no home to return to. I sat talking to one man, who told me that the difficulties and danger of life in Syria had forced him to flee. He travelled across the Mediterranean in a small boat, and then walked through ‘Albanie, Montenegro, Hungary’, and on to Calais. He said that in their town there are about 35,000 people and that about 3,000 of them have fled. Two days ago another man in the camp had found out his house had been destroyed by a bomb. Fortunately his family had already fled.

‘Here there are problems. At home there are problems. In England there are no problems. I try nearly everyday [to go to England], sometimes I try the train but it is very dangerous. People die in the trains, all the time. 5 days ago 2 people died.’

We parted, trying to not to show how shaken we were by what we had just experienced, handshakes and ‘good luck!’ and ‘see you in England!’ ‘Insh’Allah!’

As Hannah finished tracing in the streets and school of their village, one man tentatively reached for her sketch pad and pen and sat hunched over, drawing out his own memory of his village. (shown below)

The next morning we passed by the Syrian camp again to give them some photocopies we had made of the drawing. After yesterday’s highs and lows the atmosphere was slightly subdued; frustration, a sense of desperation and the desire to leave hung in the air. The man who had been shaving when we arrived the day before grabbed Hannah’s sketchbook and started rifling through it. He stopped on a sketch and pointed at one of the men.

‘This morning, he went under a lorry and made it to England’.

A few of the men accompanied us as we headed towards the ferry port to start hitchhiking back to England. We said our goodbyes, holding the uncomfortable awareness that the passports in our pockets would carry us across the channel. In stark contrast to the peril these men face every time they try to go to England, we walked over the footbridge into the port and hitched a ride back to London with no difficulty, danger or complication.