By Valeria Alice Colombo, Illustrated by Joana Maria Neves

On October 9th, the Al-Sarraj government in Tripoli launched a new code of conduct to be signed by civil rescue actors operating in the central Mediterranean. We won’t sign it. This is why.

Rescuing in the Mediterranean Sea is not the same as rescuing in other waters: it has become an act subject to suspicion, defiance and speculation by European authorities. To disincentivize the action of civil society at sea, the most vulnerable were targeted. Many of the people rescued by NGO ships in the last year have been punished with weeks of waiting at sea, on overcrowded boats in critical conditions, with unnecessary delays in granting a safe port where to disembark. All of this has happened because we, the civil society at sea, firmly refuse to bring the rescued back to Libya.

“The Libyan coastguard is doing a good job and we will keep supporting them,” declared the new Italian minister of Interior Luciana Lamorgese on September 23rdthis year, straight after the awaited meeting with her German and French counterparts in Malta. Civil society sea rescue actors in the central Mediterranean refuse cooperation with the so-called Libyan Coast Guard for a reason: because we know who they are, and what they are capable of.

Since June 2018, the International Maritime Organization recognized Tripoli as an official and reliable Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC). A MRCC is responsible of all rescue operations in a specific assigned area of international waters (also known as SAR -search and rescue- zones), providing efficient rescue interventions at sea and a port of safety. According to the United Nations however, Libya cannot be considered a port of safety.

Multiple reports from human rights monitorsstate that the so-called Libyan Coast Guard is actually formed by de factolocal militias currently involved in the country’s raging civil conflict, providing evidence of their systematic involvement in human rights violations against migrants and refugees. Regardless of such violations, European governments continue providing consistent support to the so-called Libyan Coast Guard in exchange of their commitment to intercept boats attempting to leave Libya.

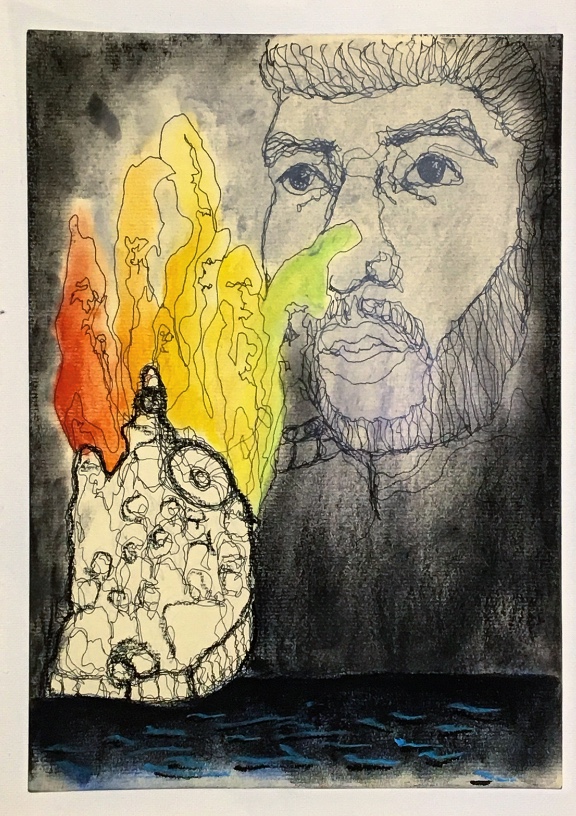

Illustrated by Joana Maria Neves, 2019

We were there on the 17thof July2018, when Open Arms found one survivor and two bodies, including a child, abandoned in open seaby the Libyans.

We were there on the 15thof August 2017, when the self-declared Libyan Coast Guard threatened the Golfo Azzurrorescue ship to change its route towards the port of Tripoli unless risking becoming a target.

We were there on the Sea Watchfast rescue boats, on the 6thof November 2017, witnessing 20 people drowning alongside the Libyan patrol boat Ras Jadir.

Tweets by Sea Watch, Open Arms and Golfo Azzurro in the above-mentioned dates, when incidents with the Libyan Coast Guard led to casualties of migrants at sea (collected by the author).

I was there myself, as part of the medic team of a humanitarian vessel, listening to the testimonies of sailors on the deck of the Nuestra Madre de Loreto, a small fishing boat from Santa Pola, Spain. “I cannot believe what I saw,” I remember the bosun telling me.“We spotted the overcrowded rubber boat at night and were reassured when the coast guards arrived”. He was in shock when referring what he and his crew had then witnessed, telling us how the so-called Libyan Coast Guard had approached the rubber dinghy only few miles from them at night.

“When they [the Libyan coast guard] reached the dinghy, they started screaming and beating people, many of whom jumped in the water, some trying to swim in our direction. There were so many people in still at sea when the patrol boat left! We only managed to rescue twelve. Most of the others, we saw drowning”.

And I was there this summer, when we crossed route with the Libyan patrol boat Tallil 267, approaching at high-speed as we were completing the evacuation of 53 people from a faltering rubber boat.

TheTallil 267is a Dutch ship known to be main vessel of Abdou al Rahman al-Milad, the commander of the regional unit of the so-called Libyan Coast Guard in Zawiyah. Some of the people we had on board after that rescue told us about him.

“There was a Libyan who lacked two phalanxes in his right hand” told us a young boy who had just come out from the Libyan Al-Nasr detention center.“This man is known by his nickname: Al Bija,” he continued, “That man was in charge of moving us to the beach, deciding who would embark to Europe and who would stay. He is a violent man, always armed; we are all afraid of him.”

(Right) Tallil 267 approaching the rubber boat after the rescue on the 12thJune 2019, picture from Colibri aircraft, Sea Watch. (Center) Abdou al-Rahman al-Milad alias al-Bija interviewed as commander of the Zawyiah Coast Guard by Amadeo Ricucci in 2017 for Italian news channel TG1, RAI. (Left) Picture of the meeting with the Libyan Coast Guard at the Italian Coastguards HQ in May 2017 from the official Italian Coastguard website. Al Bija is recognizable as the fourth man from the left.

For years Al BijaAbdou al Rahman al-Milad has been playing a double game with European authorities, managing the so-called Libyan coastguard whilst also organizing trafficking himself.

In June2017, Al Bija waslisted in the sanction listof the Security Council Committee of the United Nations for been “consistently linked with violence against migrants and other human smugglers”. At the beginning of 2017, journalist Nancy Porsiawas the first to report the testimony of whistle-blowers from the Libyan security forces in Zawyia declaring that “Al-Bija is the undisputed leader of migrant trafficking”.

Nonetheless, just a few months before the inclusion of Al-Bija’s name on the UN sanction list, and precisely on the 11thof May 2017, al-Bija attended a high-level security meeting with Italian intelligence officials in Mineo, Sicily, negotiating alongside other North-African authorities to strategize how to best block the departure of migrants from the African coasts.

This information was released by an inquiry led by Italian journalist Nello Scavofor the newspaper Avvenire, soon reaching major international media. Just a few days ago both him and Nancy Porsia were assigned personal special security by the Italian police, after receiving threats by al-Bija for their reports.

If this summer we had reached that faltering rubber boat just a few minutes later, Al Bija’s ship would have taken those 53 people back to a migrant detention center in Libya, where they would have likely been incarcerated again, detained and abused before being put on a boat once again.

Luckily enough, the militia arrived after us. Finding no one on board, they settled for taking back the engine. Why would a coast guard patrol ship be interested in retrieving the engine of a derelict rubber boat, would be a legitimate question? The answer is obvious to those who are most familiar with the situation in Libya. To use it again.

In the name of security, Europe has backtracked from its moral duty to provide safety and rescue to people running away from the hell of Libyan prisons, deciding instead to cooperate with smugglers, militias and traffickers. As the price payed is levied on human lives, it is clear to us such strategies have been far from adequate.

There is a clear reason why we will not cooperate with the Libyan Coast Guard. That is because allowing them to take migrants back to Libya is no rescue: it is an illegal action, banned by international law and the most basic human principles. This refoulment is crime against fundamental human rightswe cannot tolerate. No matter the cost.

—

This article is a Brush&Bow collaboration, first published on The Independent on the 24/10/2019.