In November 2015 we spent time in Lesbos, speaking with refugees as they made the perilous crossing from Turkey to Greece, and found themselves stuck in limbo in Moria refugee camp, hopes and expectations dashed. This is the illustrated conversation we had with a group of Pakistani men.

Images and article originally published on the New Internationalist.

Written by Harriet Paintin, illustrated by Hannah Kirmes-Daly.

‘Leaving home is the most difficult thing… As soon as you leave, it hits you how much you miss everyone. You know that they are worrying about you every step of the way, and the journey is so dangerous. Those who make this journey are playing with their lives.’

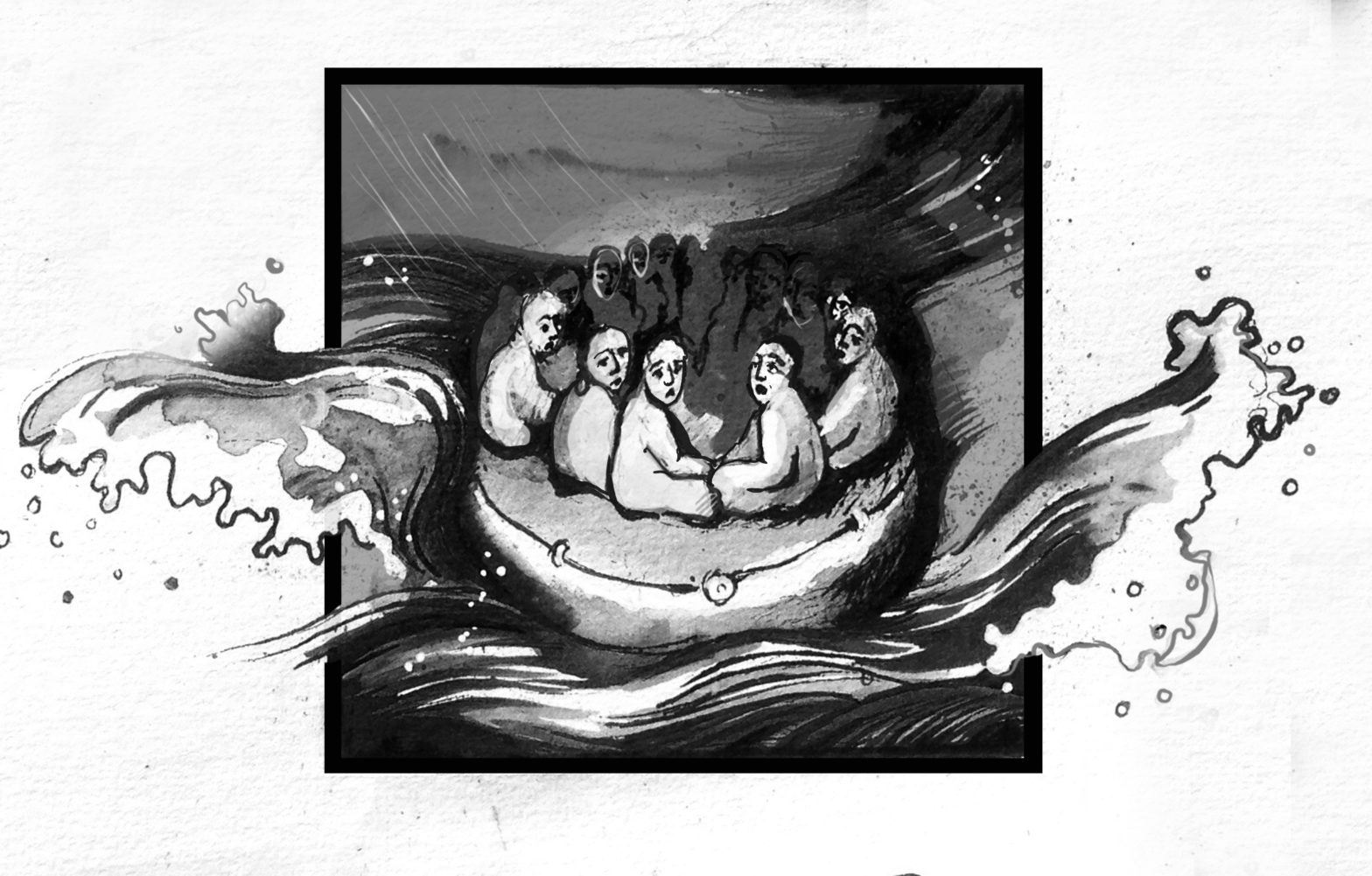

These are the words of Ali, a young man who made the journey to Lesvos with his four friends from the same small village in Pakistan. They spent 10 days in Moria registration camp, where the numerous Pakistanis, Afghans, and other ‘non-Syrians’ waited for days in deplorable conditions for the necessary papers to continue their journeys.

‘Here (in Europe), now, my heart is heavy and I am worried. People from home phone me and ask if I’m alright, and I lie and tell them everything is fine.’

‘In Pakistan we were always so worried about money. We could never save enough to cover the months when our businesses failed. Our families are so big and only one or two people are able to earn money, so overall the family does not have a lot of money.’

‘Those that can earn decide to go to other countries, where they can earn more,’ Vafa, one of the group explained, quietly and seriously. ‘No Pakistani people are making this journey for themselves. At home everyone is depending on us. Our families will only eat when we are earning money.’

Their eyes lit up as they remembered their home, the small mud houses next to a river, and fields where people grow rice and wheat. They became more and more animated, speaking faster and louder.

The decision to leave home, all that you know, and risk everything is always difficult. Far from the leaping at the opportunity to make a brighter future in Europe, these men described the agonising moment they made the choice.

‘We were all sat together, by the river… We were feeling so much pressure, we had to do something! So we decided to leave, to go to Europe. A week later, we left.’

Ali took a deep breath and talked about how the first part of the journey, from Pakistan to Tehran, had been easy, as they had a visa for Iran, but then it became much more dangerous.

‘When we arrived in Tehran we phoned one of the smugglers, who came to meet us. He took us to a deserted spot outside the city and put us into the back of a small container lorry. There were 22 of us inside. It was so cramped we couldn’t move.’ They all moved closely together to show us how they were crammed in. ‘The only oxygen came in through a tiny hole at the top.’ Ali demonstrated how they would stand up, put their face to the small hole for a brief moment, then sit back down.

‘We stayed in this vehicle for 14 hours, until we arrived at a small village, next to the border, where there were many big mountains. We got out, and there was a small house where the mafia man shut us all inside. It was a mud house.’

‘Like the kind made for animals, there was nothing inside, no mattresses, nothing. We stayed inside for the whole night.’

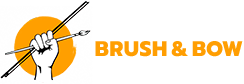

‘In the morning we got into another lorry, just like the one from the day before, which took us high into the mountains until the road ended. From here we had to go onwards by foot. There were smugglers there who showed us the way’

‘Often people would fall here, and below we could see so many dead bodies of young men who had fallen…’ Vafa described how his heart was saying “turn around and go back”, but when I thought about my family at home my courage would come back to me and I carried on.’

‘Across the border there was another small house, where the smugglers shut us inside for two days. It was so dirty and smelly and there were 200 of us inside. The smugglers came and took money from us, they emptied our pockets and took everything. By now we had each paid around $3,000.’

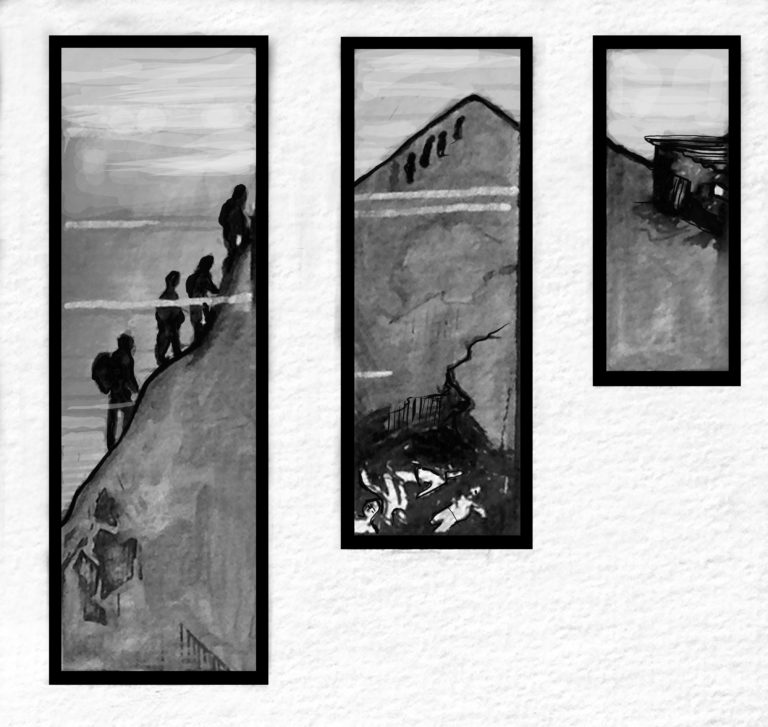

Ali described how they crossed Turkey by foot until they reached the sea. ‘A Turkish smuggler told us to come with him, and we followed him back up into the mountains to the place where they keep the rubber boats, deflated, inside big cotton sheets. He told us to pick it up and carry it down to the shore. We pumped up the boat and put it in the water.’

‘The wind and the waves were strong, and when we got into the boat water started coming in straight away…’

‘I was emptying it,’ interjected Jamal, miming scooping water out of a boat

‘During the whole journey we were praying and taking the names of our mothers and fathers,’ said Abdul quietly at my side.

Vafa piped up, smiling, ‘I was eating biscuits! Before dying, you must eat something!’ All of them laughed, and told us that the man driving the boat kept letting go of the steering stick to eat biscuits. They shouted at him: “Stop that and drive the boat!”’ The mood had lightened, and we all laughed.

‘So, what happened when you arrived?’

Jamal replied, ‘The first thing I did was to give thanks to god. Our clothes were soaking wet; we threw them away! We were so happy. At this time we really needed some love and care, and some really nice people were there, they gave us water and juice. There were also media people who took everybody’s photos, they were filming and asking people who spoke English, “How did you get here, did you have problems?” We didn’t like these people, we told them we didn’t speak any English.’

Unfortunately for these five men, the journey was far from finished. As they headed through Europe, towards the winter, they were constantly aware that their journey could come to an abrupt end. During our previous conversations they had pressed for information about which countries they could safely enter without the threat of deportation.

‘They should give this information to people who are setting off on this journey. You won’t get anything, only Syrian people will. The people who arrive here have had such a difficult journey. People sell everything they have to get the money for this journey, and then they get deported and they return to nothing, zero, to start their lives again from scratch.’