Written by Roshan De Stone and Hannah Kirmes-Daly.

Curving our way through the mountains, we arrived to the Italy’s autonomous region of Trento. Exiting the train station, we were greeted by a plush green park, filled with elderly Italian couples and young male migrants sitting in the sun. We had come to visit the Bruno Social Centre, a place of self-organisation and co-operation working toward making Trento a better, a more inclusive, city. On our way, wandering through the city centre’s picturesque plaza, we heard a women singing , a cap in hand. Her voice was soft, yet strong and passers-by walked past without seeming to hear her.

Dropping a few coins in her hat, we learned that her name was Benedetta, or Blessing in English, and she had travelled from Nigeria to try and make some money to send back home to her sick mother and two children: “ I just want them to be able to go to school” she said. She explained how she had looked for work, but her lack of Italian, black skin, and immigration status had made it nearly impossible to find anything other than sex work or begging. “For most people like me, sex is the only way they can make money.” With 80% of Nigerian women arriving in Italy ending up in the sex trade, she is not wrong. She continued to tell us however, that as a Christian, her belief made her feel she could not bring herself to offer sex for money or just beg. “I want to work”. Owning next to nothing, singing was one of the few things she could offer. Despite the hardship she had suffered on her journey to Italy, she had a strong spirit: telling us that she believed that Jesus would bring justice to all in the end.

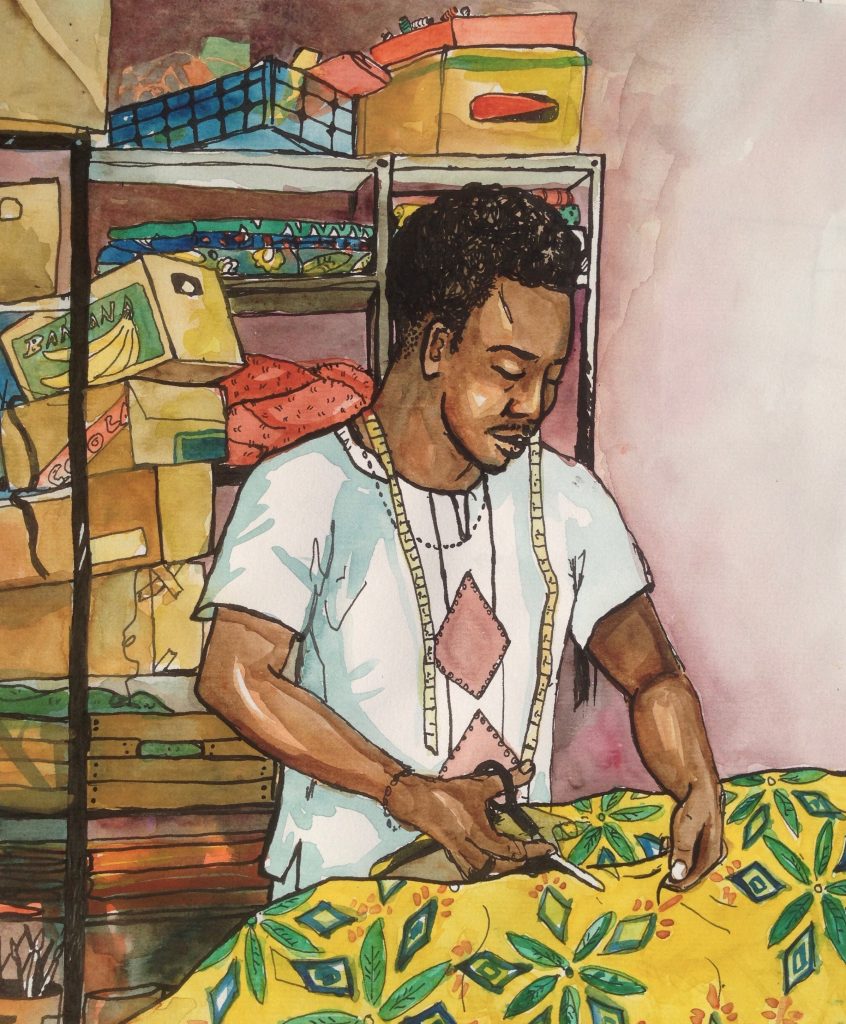

Arriving at Bruno Social Centre, we were led up three flights of stairs to a tailor shop. Senegalese music rose above the hum of sewing machines. Four men, deep in concentration lent over their sewing machines, stitching brightly coloured cloth. Vividly patterned materials garnered in bright blues, greens, yellows and red were splashed across every surface and dresses, shirts and trousers hung from the ceiling. Scissors, measuring tapes, piles of cloth and pens cluttered every free surface. This was a tailor workspace run by professional tailors who also happened to be refugees and migrants.

Illustrated by Roshan de Stone.

Set up in 2011 by members of the Bruno Social Centre, the tailors paid for their electricity but were given the space for free to make a workshop. Six years later, the workspace had blossomed. One of the tailors named Antony gave us a tour, explaining what each tailors’ specialty was: design, intricate needlework, fittings, the list went on. He explained how they took individualized orders from customers at the local market, or from people who had heard of their work through word of mouth. “We don’t just make something, we think before making it, what is the best thing about that person and then we try to bring out the best so when people see it they think, wow that’s nice!”.

The fabrics were ordered from different countries in Africa: “Italy doesn’t have fabrics like this,” Antony laughed. “So when Italian people wear our clothes they look like African and they think wow African material! They will look African and then they will ask where do they make these and think…I need something like this!”. The pride that Antony held in his work shone through the enthusiasm in his voice. Clara, a recipient of one of the tailor’s dresses, enthused about what opportunity this provided for people to use the skills they already have to bring something positive to Italy.

Illustrated by Hannah Kirmes-Daly

The quality of the products made by the tailors showed how how talented and resourceful people could be when given a little support – even just a safe space to work. Whilst the local Trentino government do provide minimal job seeking support for refugees and migrants, the productivity of the workshop raised the question of what might happen if the government gave as much money toward employment support as they do toward containing, detaining and deporting people.

Uplifted by the interaction, we left, discussing how inspiring the tailors were: not only working but creating trade links with countries in Africa, bringing new cultural attire to those living in Trento. The success stories of southern towns such as Riace and Sant’Alessio, whose policy to invest education, training and financial support to migrants and refugees led to the stimulation of a dying economy, illustrate that it is not just naive idealism to think that a radical shift in Italian – and EU – policy could have a major impact in bolstering the economy and enriching the cultural fabric of the union. In Riace and Sant’Alessio, this was not only a humanitarian response to a humanitarian crisis, it was also an economic and cultural response. It created jobs for both refugees and migrants as well as locals, consequently helping to stem the flow of young Italians in the south seeking work in the more prosperous north and thus “bringing the towns back to life.”

As more and more entrepreneurial initiatives are started by migrants and refugees, often with the help of non-governmental organizations, this is an alternative that European countries should pay attention to and think of as a viable alternative to the aggressive and failed attempts to exclude, detain and deport.