A doctor’s account on board of the Mediterranean rescue ship Alan Kurdi.

By Valeria Alice Colombo, Illustrations by Francesco Piobicchi

Lesvos, June 2019

In the morning of 3rdof April 2019, the search & rescue ship Alan Kurdi rescued 63 people from an overcrowded rubber boat in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, 20 nautical miles from the Libyan coastal city of Zuwara. I was the medic on board.

The Alan Kurdi is the old German vessel of one of the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) performing search and rescue (SAR) operations in the central Mediterranean. SAR missions in this area are officially assigned to the Libyan coast guard, who responds to the government of Tripoli and operates thanks to training and support provided by European governments. Their mission is to intercept migrants leaving the Libyan coasts and bring them back to Libya’s detention centers, despite the United Nations have declared Libya is not a safe country of return.

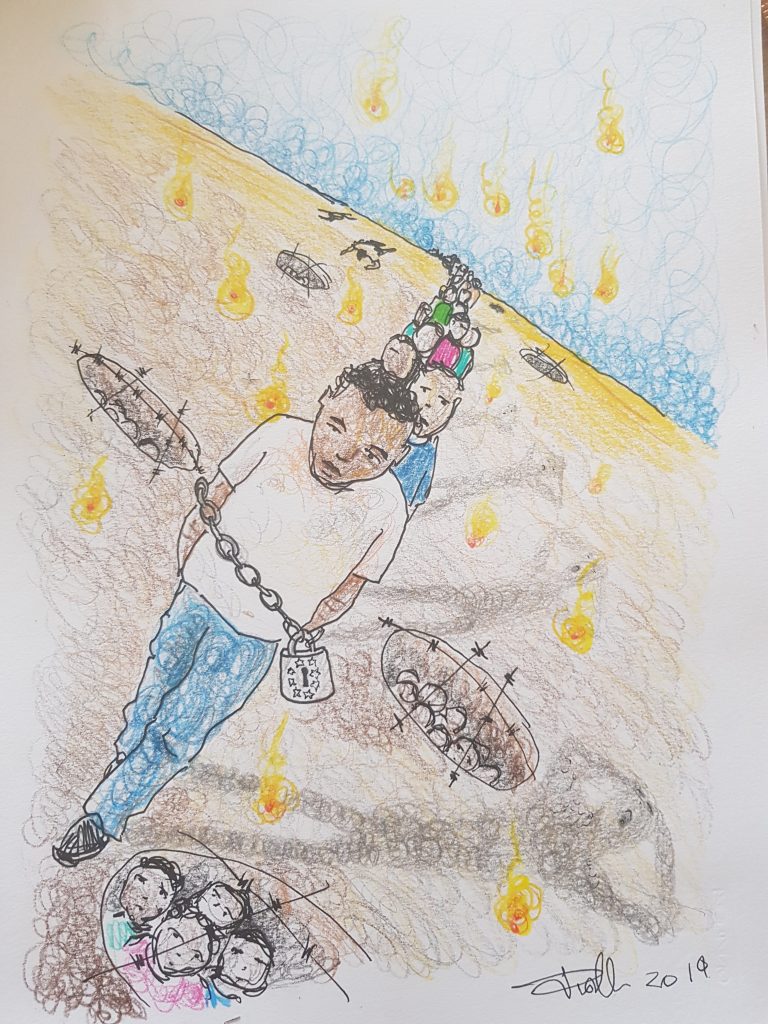

“Piove plastica fusa” (Its raining melted plastic). | Illustration by social artist and Brush&Bow contributor Francesco Piobicchi.

On the very same day of the rescue, the Libyan National Army (LNA) guided by Khalifa Haftar moved to attack the capital city of Tripoli, in an attempt to overthrow the internationally recognized government of Libya. Such conflict is only the latest chapter of Libya’s recent destabilization and civil war. Authorities in Tripoli are also in charge of all SAR operations in Libyan waters, exactly where the overcrowded rubber boat was being found. As often before, and even more so on that day, nobody in Tripoli attended our SAR alerts and communications.

Once all 63 people were on board, Malta and Italy refused to provide us a harbor where to disembark them. “Our ports are closed to migrants”, proudly declared the Italian Minister of Internal Affaires. In Brussels, the European governments entered into negotiation to organize a redistribution of these few asylum seekers, a process that kept us in international waters for ten days. Enough time to get know each other.

While the whole of Europe was speaking about the castaways we had on board, we were the only ones hearing from them. And that’s how we came to know the common horrible past of those people rescued on that broken rubber dinghy. For most of them, troubles began in Agadez, Niger. That’s what Jean tells us.

He comes from Cameroon and is a sharp, cultured man. He enjoys impressing the crew singing liturgical chores in Latin, evocating some proverbial phrases in German and sharing opinions about European politics. He tells us about his long journey from his homeland through Libya. While escaping from the uprising violent civil conflict affecting his homeland, he found himself in the hands of a Boga. A Boga, or pusher man, is a man in charge of the ‘transition’, as Jean calls it; the smuggling of black people from Agadez to Sabha, in Fezzan, the southwestern region of Libya. The Bogasare human traffickers.

On the road to Sabha, all along the desert, Jean could see the ‘transithouses’where the human traffickers sell black people as slaves to the Arabs. “Sabah is the more dangerous town in Libya”, Jean says, the main market of black slaves. He explained how he had never seen such atrocities before. He himself passed through a ‘transit house’, sold to the Libyans.

On the deck of the Alan Kurdi, he tells us how he and other people with him were systematically abused and tortured, in order to make their families pay a ransom. They got whipped under their feet until they bled and then forced to stand and jump. Jean vividly described scenes from an inhuman place. How they were tortured with electricity and fire, or crushed to the floor under the weight of heavy objects. They were forced to beat each other; if they don’t beat strong enough, they would get punished. Some people Jean met in the transit housedied in front of his eyes after days of torture. Their bodies abandoned in the desert.

After a horrible, endless time in Sabah, Jean is brought away to the north, just to be taken to another ‘transit house’ in Bani Waled. Bani Waled, tells Jean, is like a concentration camp. Every night he could see people chained one to each other, leaving and coming back exhausted, after days of forced work. The torture is the same as in Sabha. Survival is the only instinct that remains to people after spending time here. Some survive by stealing food from the guard’ dogs or by drinking their own urine. Every day the guards take some of the prisoners to torture them for hours while calling the families by phone, cutting wounds on their legs, breaking their arms, burning their genitals with flaming plastic until they obtain the ransom.

“Speriamo che non sia il mio turno” (Let’s hope its not my turn) | Illustration by social artist & Brush&Bow contributor Francesco Piobicchi.

Again, he saw people dying in front of his eyes, beaten to death when they could not even raise their hands to protect themselves. Again, bodies abandoned in the desert.

Jean tells a story that everyone who was rescued on the Alan Kurdi knows well. All the rescued on the Alan Kurdi experienced the arbitrary detention Jean talks about. Every women, man and child on the boat has been an arbitrary abductee in an overcrowded room, had been beaten and starved. Many have died before reaching the sea. They are the ones to have escaped. And everyone who tries escaping risks being taken back to the ‘transit house’. Libya is a huge jailhouse for migrants.

The borders in the country are controlled by military patrolling troops, recycled as militias searching for prisoners to blackmail. Black people in Libya cannot move freely anywhere in the country without risking being abducted; traffickers transfer them from one place to the other, hidden in cargo trucks or dressed like women, as policemen at checkpoints are not allowed to remove the niqab off women. They have no kind of document, confiscated by the bogas during their crossing of the desert. They have no money, as they are systematically robed of the very few they succeed to earn.

But then why do so many migrants end up in Libya in the first place?

In those ten days of waiting on the Alan Kurdi, I heard the story of women who had arrived to Libya deceived by a job proposition, mostly as housekeepers. Elisabeth is the first of seven sisters. Her father died when she was a child. She couldn’t finish secondary school and had to start working to help her mother. At twenty-five she succeeded in enrolling at a professional fashion-design course in Lagos. Still once graduated, she couldn’t find a suitable job in Nigeria. Some friends told her that in the northern African countries she could easily work as fashion designer and at the same time support her family by sending money back home.

One day she got a ride in a crowded car travelling to Libya. She recalls the journey very well, and told me how they stopped in the desert just to make a few stops, to drink and rest. Once across the Libyan border, one of these stops transformed in a long-lasting trap. She was taken to a ‘connection house’, where women are used as sex slaves. There were many other women there. She soon learned that if she refused, she would be tortured. If she tried to escape, she would be tortured. Sometimes, she would be tortured for no reason at all.

Elizabeth spent two years in a ‘connection house’,until she was sold to a local Libyan man to work as a domestic worker. She was taken to Tripoli, where black people are employed in housekeeping or construction. They earn little money, barely enough for their own food. And yet at any moment, the self-declared local police may stop them arbitrarily and take them to a detention center.That’s what happened to Elisabeth, as she was doing the grocery for her owner.

For black migrants, there is no way out from Libya. If your skin is black, you are a slave or a prisoner.

What seems to be misunderstood in the many current debates about the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the Mediterranean are the reasons moving people from sub-Saharan African countries to Libya. It is mostly intimated that people on rubber or wooden boats sailing hopelessly to Europe have come to Libya to cross the sea and reach Europe. But that is incorrect.

Benjamin used to work in fishing logistic and distribution in Nigeria, his homeland. He maintains that a professional experience in a foreign country could fortify his professional skills. He was kidnapped as he was travelling to Tunisia. He has been enslaved for two years.

Elliot went to Libya to work as housekeeper, as she could not find any job in her country. She brings on her skin the signs of years of tortures and abuses.

Marc was working in the mines of Chad to earn money to send home to Cameroon. He was nineteen when he was kidnapped andtrafficked to Libya. Today he is twenty-two, and has just managed to escape Libya on an overcrowded broken rubber boat.

Jean, Elizabeth, Benjamin, Elliot, Marc, they were all chasing the illusion of a better life in the northern countries of their continent, and not across the sea. In Europe nobody knows this, because nobody asks them. Surely the prospect of reaching Europe is attractive to many. But it should not be seen as the main motivation for all. Most people take the sea because they have no other way out from a country, Libya, where they are systematically tortured and imprisoned as slaves. Many of them have never seen the sea before. But they still take the risk of drowning because that is the only option available to break free from Libya.

This article was first published on the 7th July 2019 by Brush&Bow on La Stampa and on the 5th of August 2019 on OpenDemocracy.