In Lebanon, a women-only group of migrant domestic workers have come together to fight for rights in the workplace.

This article was originally published on Open Demoracy’s North Africa West Asia page.

FB: /NAWAoD – Tw: @NAWAoD

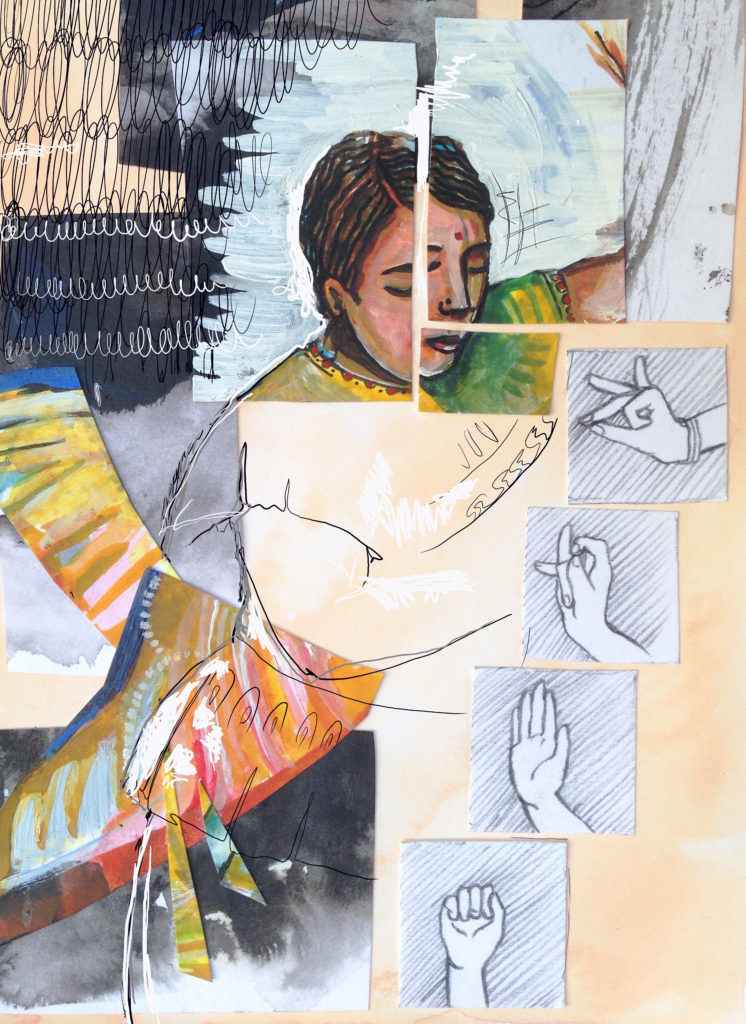

As one dance ended and the audience burst into applause, loud Ivorian beats began to blare from the speaker in preparation for the next performance. The room was full of beautifully dressed women in saris, pagnes, jeans and shiny sequined tops, jostling for space in the packed theatre.

Before the last dance, Rose took the stage, switching fluently between English and French. “I want everyone to know that we are human beings. That we have skills and dreams other than just working in peoples houses.”

It might not seem a lot to ask for, but in Lebanon where these women work, their most basic human rights are systematically violated. Just two years ago, domestic workers would face detention and deportation if they were found to have a relationship. “They even want to control who we love and when we love”, Rose told us.

Migrant Domestic Workers in Lebanon

There are an estimated 250,000 migrant domestic workers in Lebanon, making up nearly 10% of the country’s female population.

Excluded from the national labour law, migrant domestic workers are forced to work under the infamous Kafala system, a system of sponsorship that binds an employee to their employer in a slave-like relationship. Under Kafala, the right of an employee to enter, work and reside in Lebanon is utterly dependent on their employer.

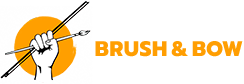

Illustrated by Hannah Kirmes-Daly

The Alliance of Migrant Domestic Workers

In 2016 a group of female domestic workers came together to form the Alliance of Migrant Domestic Workers. Amongst the members of the Alliance, the freedom to choose one’s own narrative is paramount. “When people are always telling you what to do, it is so important that in our own struggle, our voices are heard.”

The women who make up this group are formidable. Some of them having been activists for over 20 years in the hardest conditions as Lebanese authorities do not recognise the right for migrant workers to unionise. Their strength is not only evident through their activism, but also in their ability to create a safe space for domestic migrants workers to come together and share their experiences. The Alliance meets on Sundays, with members using their only day off to support others.

“But we must be careful”, added Jenna, as she tucked her hair behind her ear. “We cannot be aggressive. We cannot confront authorities directly or else we will always be the ones to lose.” Her words are laced with the memory of her colleagues, Sujana Rana and Roja “Rosie” Maya Limbu, who were detained and deported in 2016 for their activism. “Their activism was too aggressive. And even though Sujana was well known and had worked with so many different NGO’s, in the end none of them could help her when she got detained.”

“But we have each other”, Rose added, gesturing proudly at the other members of the Alliance. Focusing on grassroots community outreach activities, the Alliance builds trust and solidarity amongst domestic migrant workers throughout Lebanon.

“We do activities that involve everyone using drama, music and dance” said Maria, a worker from Ivory Coast. Partnered with a local theatre in Beirut, the Alliance is preparing a drama show to put on stage. “We don’t all speak the same language but we share the same experiences and theatre is a way of sharing our stories.” Pointing at her heart she continued, “Even if we don’t speak the same language, we understand each other here.”

Learning how to work with ‘madame’ is another key thing that the group do. Helping new workers to know their rights, face the struggles of domestic labour and deal with their employers. “For example,” Maria told us, “perhaps a maid has not been paid for 6 months, we would try and help her ask her madame for the money she is owed without causing confrontation.”

Withholding salary seems to be an ordinary practice amongst employers, a practice also recommended by recruitment agencies when advising employers on how to treat their workers. In the many conversations we held with domestic workers, it appeared that a ‘good employer’ is someone who does not physically or sexually abuse their maid.

During an undercover interview at a recruitment agency in Tripoli, we enquired about the process to hire a maid. When we asked whether she was entitled to any holidays we were met with laughter: “No, no day off. And if she is sick then you can send her back here and we will get you another one.” We were also told not to give her a telephone “it will just distract her” and to lock her in the house until we trusted her.

Despite the ever-uphill battle, these women, many of whom have worked for more than 20 years under Lebanon’s abusive kafala system, are determined to bring their campaign onwards. “We know our limits, but we will not stop. It may be too late for us, but we must change things for the younger women coming in.”

Where it is currently too dangerous for domestic migrant workers to speak out, the international community must intervene, pushing Lebanon to ratify ILO’s Convention No. 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers. But aware of the timings and illusions of politics, the women of the Alliance are wasting no time, keen to take the struggle in their own hands.

Before leaving the theatre, Serena, a dancer in the performance spoke to us: “the realization that support is available through shared experience can be so much more powerful and long lasting than any sit-in or demonstration. This is no simple political game. Our lives are on the frontline”.

Illustrated by David Suber